…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

The Nautical Almanac and associated publications

The published output of the Royal Observatory falls into six categories:

Observations and associated catalogues, Annals, Bulletins and Circulars

Annual Reports

Scientific Papers

The Nautical Almanac and associated tables, along with the later spin off volumes

Notes, Reports, Manuals, house journals, etc

Visitor Guides and material for non-professionals

This section deals with the The Nautical Almanac and associated publications.

Nevil Maskelyne, the fifth Astronomer Royal. Engraved from a pastel drawing by John Russell and published by J. Asperne, 1 March 1804

Introduction

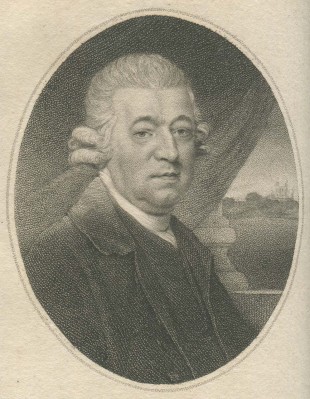

Henry Andrews (1744–1820), who worked as a computer on the Almanac from 1768 to 1815. Reproduced from a photograph of an original etching in the possession of Queen Victoria and published in the form of a postcard by The London Stereoscopic Company in the early twentieth century

Rev. Malachy Hitchins (1741-1809), comparer for the Nautical Almanac from 1767 until his death in 1809. Hitchins also spent just under four months covering for Maskelyne's assistant William Bayly while he was away in Norway observing the 1769 Transit of Venus. Painting by John Opie, 18th century. Image courtesy of Andrew Maden

The first edition was for the year 1767 and contained a preface written by Nevil Maskelyne, the Astronomer Royal. Although it carries the publication date of 1766, Howse (1989 p.86) states that copies were not recieved from the printer until 6 January 1767.

It contained amongst other things, a set of tables showing the position of the Moon during 1767. The Moon’s angular position relative to nearby bright stars was listed at three-hourly intervals of Greenwich time. For both this and the subsequent nine editions, the lunar positions were computed from tables published by Tobias Mayer. To ensure their accuracy, the computations were performed in duplicate by two independent computers and then compared for consistency by a third person known as a comparer.

To determine his longitude, a sailor had to measure the angle between the centre of the Moon and a listed star (the lunar-distance) along with both their altitudes. Next, he had to calculate his own local time and correct the Moon’s position for the twin effects of parallax and refraction. The time this corresponded to at Greenwich was then determined from the Nautical Almanac. From the difference between this and his local time, he was able to calculate his difference in longitude from the Meridian of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich. To make the whole process as simple as possible, Maskelyne simultaneously published the Tables Requisite, containing amongst other things, tables to correct for the effects of refraction and parallax, together with instructions and worked examples of how to use them.

Annual volumes are still produced by the Nautical Almanac Office, though the lunar-distances, which were so key in the early years ceased to be published after the volume for 1906.

Responsibility for the Almanac

Overseeing the production of the Almanac was originally the responsibility of the Astronomer Royal acting on behalf of the Commissioners of the Board of Longitude. In 1818 this responsibility passed to Thomas Young, holder of the new post of Superintendent, who reported to the Board of Longitude. Young was succeeded in 1829 by John Pond, the Astronomer Royal. Pond was rapidly followed in 1831 by William Stratford. It was Stratford, who in 1832, set up the Nautical Almanac Office (NAO) to oversee the Almanac’s production, with the Superintendent now reporting to the Admiralty. He introduced changes for the 1834 edition, the most significant being the use of Greenwich Mean Time in place of apparent time.

In 1937, HMNAO as it had by then become known, became part of the Royal Observatory. It was evacuated to bath in 1939. It relocated to Herstmonceux, in 1948, and then to Cambridge in 1990. When the Observatory was closed down in 1998, it was transferred to the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory. In December 2006, it was transferred again, this time to the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office.

The associated volumes

In addition to producing the Nautical Almanac HMNAO produced numerous other associated volumes whilst part of the Royal Observatory. These are listed by George Wilkins in appendix F3 of his Personal History of H.M. Nautical Almanac Office

On-line volumes of the Nautical Almanac

Many of the older editions of the Nautical Almanac are now available on-line. At present, little is known about the reasons why second editions were printed, or for which years they exist. They may have been reprinted because stocks ran out, or perhaps more likely, it was to correct errors. Despite all the checks that were in place, errors did creep in, for which errata were issued in subsequent volumes. The volume for 1784 (published in 1779) contained a serious misprint on p.98 where in the Title of the Equation of Time for September, the word Add was printed instead of Subtract, leading to a possible error of over 20 minutes in time. A second and corrected edition was published in 1784, but with a slightly different preamble, the wording of which suggests that the volume was not in fact published until after 6 March.

(a) Second edition

(b) Click here for second edtition

Published in 1851, Appendices to various nautical almanacs between the years 1834 and 1854, is a republication in more permanent form of the appendices which appeared in the volumes from 1835 and 1854.

The Tables Requisite

First edition, 1766

Second edition, 1781

Third edition, 1802

Explanatory Supplement

International cooperation

At the 1911 Congress Internationale des Ephemerides in Paris, the five principal ephemeris-producing nations (France, Germany, Great Britain, Spain and the United States) agreed to co-operate in the production of almanac data, with the aims of avoiding duplication of effort and of standardising the basis upon which the ephemerides were computed. This arrangement came fully into force in the publications for 1916.

In France, the Ephemerides were published in a volume called La Connaissance des temps, whose name varied slightly over time. Most editions are available online.

La Connaissance des temps for the years 1679–1803

Ephémérides astronomiques: Annuaire du Bureau des longitudes for the years 1985–2014

Some volumes (mainly 1917 and earlier) of the American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac are also available on line. First published for the year 1855, it has been known as the Astronomical Almanac for the years 1981 onwards.

American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac

Further Reading

The Bicentenary of the Nautical Almanac. Donald Sadler, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 8, p.161 (1967)

The making of astronomical tables in HM Nautical Almanac Office, George Wilkins, The History of Mathematical Tables: From Sumer to Spreadsheets (Oxford, 2003)

© 2014 – 2026 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan