…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

The solar eclipse of 30 June 1954

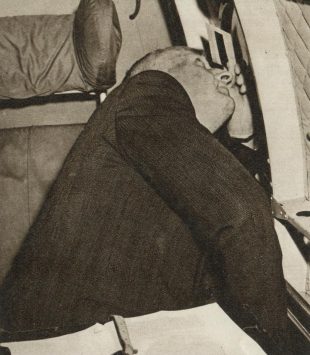

The Astronomer Royal, Sir Harold Spencer Jones (left) and Donald Sadler, the Superintendent of H.M. Nautical Almanac Office posing for the press in front of an aircraft at R.A.F. Hendon on the morning of the 29 June before flying to R.A.F. Leuchars in Scotland from where they were due to takeoff to view the eclipse the following morning

Unlike the eclipses of 1927 and 1999 where the path of totality crossed mainland Britain, during the 1954 eclipse it only crossed Unst, the most northerly of the Shetland Islands – a location that was not particularly favourable for a scientific expedition.

Instead, the Royal Observatory sent several members of its staff on expeditions to Sweden whilst others (including the Astronomer Royal) had the opportunity to observe the spectacle of totality from the air. Meanwhile, those staff who remained behind at Herstmonceux, Abinger and Greenwich were able to see a partial eclipse with about 70% of the Sun being obscured at mid-eclipse.

As with previous eclipse expeditions, the Royal Observatory planned its programme in conjunction with other British observatories through the auspices of the Joint Permanent Eclipse Committee (a joint committee of the Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society). Other UK expeditions were sent from the Observatories of Cambridge, St. Andrews, and London Universities.

Parties from other countries also went to Sweden, including ones from France, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Finland and the United States.

The sites chosen by the Royal Observatory were on islands just off Sweden's east and west coasts where the prospects were more favourable than on the mainland with a roughly 50% chance of the skies being clear.

The Astronomer Royal explained the aims of the Observatory's expeditions to the Board of Visitors in his 1954 Report and the outcomes of the expeditions in his report for the following year. The text from these is transcribed below. There were also reports of the eclipse in the British Press as well as in a book by Eric Cropper an R.A.F. navigator who was tasked with arranging the flight for the Astronomer Royal (more on these below).

Aims of the expeditions

Amongst the areas set to be investigated were:

- the structure and nature of the the solar corona

- the temperature and other properties of the solar chromosphere

- the deflection of light by the Sun (the 'Einstein shift')

- the daytime aurora

- radio emissions from the Sun

In addition, because the track of totality extended across three continents it was hoped to obtain more accurate information about the shape of the earth as observations of the eclipse observations would provide extremely accurate positions of the moon allowing it to be used as an intermediary through which existing geodetic triangulations could be tied together.

The Astronomer Royal's pre-eclipse report

The following text is taken from the 1954 Report of the Astronomer Royal to the Board of Visitors.

'The Field Equatorial belonging to the Joint Permanent Eclipse Committee has had its centre section bored out to take the centre section of the 21-ft. telescope, of 7 inches aperture, which had been used with a coelostat at some previous eclipses. On this occasion it is intended to use it for studying the Einstein effect; the increased scale and the smaller aperture-ratio, compared with those of the Carte du Ciel lens for which the mounting was designed, should be advantageous. The Equatorial was designed for latitudes up to 30º; a large pedestal has been constructed of angle-iron to convert it for use in latitude 59º. The thrust-supports for the polar axis have been strengthened, as the load on them is very much increased. The cable-release motor has been moved so as to shorten the cable as much as possible, with a view to reducing the whip. A new rotary exposing shutter, over the object glass, has been made and operates so smoothly as to be without visible effect on the stability of the images. The instrument was erected in November in the Thompson dome, whose dome-motor had been re-wound and re-mounted for this purpose, and the performance of the lens was found to justify the use of 15-inch plates covering 3½º. A new double plate-holder has been made to facilitate a quick change of plates during the eclipse. A light framework hut, of tubular scaffolding, large enough to cover the telescope completely in the positions in which it will be used, was erected at Herstmonceux and covered with waterproof canvas; it will serve both as a windbreak during actual observations (the instrument being somewhat lacking in rigidity), and also for protection from the weather, especially during the months that it will have to stay in position after the eclipse if the eclipse results themselves are satisfactory. It is intended to obtain during the eclipse two plates, on each of which is photographed the eclipse field and a selected nearby comparison field; the same fields will subsequently be photographed on comparison plates, if successful observations are made during the eclipse. The comparison field will provide a determination of the difference of scale, which will then be used for the reduction of the eclipse field. The mounting and tent were both dismantled at the end of April for packing and shipment to Sydkoster, (Sweden). The observing party will consist of Mr. Gold, Dr. Hunter, and two volunteers, Mr. Bastin and Dr. Sciama from Cambridge University.

Two of the cine camera assemblies used for the 1952 eclipse have been over-hauled; one will be used by Mr. Pope for the Atkinson method, just outside the zone of totality at Simrislund on the Swedish mainland, and the other by Dr. Atkinson for the Banachiewicz method, near the central line at Persnäs (Öland). A direct comparison of the two methods, both as to ease of reduction and as to final accuracy, will be valuable. The camera mechanisms have been carefully reconditioned and readjusted, to eliminate a fault which had given some trouble before; they have then to be squared on afresh. Unmounted gelatine filters, close to the focal plane, are being substituted for glass-mounted ones immediately outside the fiducial-mark lenses, as this arrangement should in principle be slightly preferable.

A visit was paid to Sweden by Mr. Gold, who selected sites for the three expeditions and made various local arrangements.'

The Astronomer Royal's post-eclipse report

The following text is taken from the 1955 Report of the Astronomer Royal to the Board of Visitors.

'The 7-inch telescope of 21-ft. focus intended for studying the gravitational deflexion of light at this eclipse was erected on site in early June inside the tented framework hut described in the last Report. The party consisted of Mr. T. Gold, Dr. A. Hunter, and two volunteers, Dr. E. W. Bastin and Dr. D. W. Sciama. The site chosen, at the northern boundary of a small pine-wood on the island of Syd Koster, some 10 miles off the mainland near Stromstad, Sweden, was selected to minimize the hazards from wind and from convection currents rising from the rock of which the island is largely composed.

Preparations on the site on Syd Koster island extended over five weeks. The sky, though overcast at dawn on the day of the eclipse, gradually improved there-after, and frequent views of the diminishing crescent were obtained during the early phases of the eclipse.. At second contact, however, the sky was still covered with thin high cloud, and low fracto-cumulus crossed the field frequently during totality. Neither prevented a good view of the typical "minimum" corona, but there was clearly little hope of securing any usable star images in these conditions. A modified programme was, however, carried through, exposures on the eclipse field and on a nearby comparison field being made on one plate only instead of the two it had been intended to use if conditions were favourable. As was inevitable in the circumstances, the photograph proved to be severely fogged by coronal light scattered in the cloud, and only the bright stars near the edge of the field produced visible images on the plate. The object of the expedition was therefore not attained and the equipment was dismantled and brought back to England.

The photographic density on the eclipse plate varies from about 2 at the edge to nearly 5 in the inner corona. By contact printing through a rotation sector suitably graded in aperture a representation of the corona that is pictorially satisfactory can be obtained. This shows remarkably symmetrical equatorial streamers, extending to more than four radii from the limb, sharply differentiated from the short polar plumes which border the limb at latitudes higher than 60°. The eclipse occurred at the exact epoch of minimum solar activity, as nearly as that can be determined, and at a time when the Sun was completely free from spots so that the corona was unusually free from the disturbances that occur at periods that are richer in sunspots. The axis of symmetry of the elongated streamers coincides, within the uncertainty of measurement, with the normal to the projection of the Sun's axis. If the exactness of this coincidence is more than a chance effect, this shows that those outer coronal regions are under the control of the Sun rotating deep within.

Two small expeditions were sent to Sweden to make observations of the position of the Moon for geodetic purposes. One, under Dr. Atkinson, was stationed on the island of Öland, off the east coast of Sweden, near the central line of totality, to make observations by the Banachiewicz method. The other, under Mr. Pope, was stationed on the mainland near the east coast, just south of the zone of totality, to make observations by the Atkinson method. Neither expedition was able to obtain observations during the eclipse because of clouds.

Spencer Jones viewing the eclipse through one of the aircraft windows. From the 10 July edition of The Illustrated London News

Through the courtesy of the Royal Air Force, the Astronomer Royal and Mr. Sadler obtained an excellent view of the eclipse from a Hastings aircraft. The aircraft reached the central line of totality to the south-west of Iceland and flew eastwards along the line, thereby adding 22s to the duration of totality. An excellent view was obtained of the shadow of the Moon thrown on the uniform cloud layer beneath the aircraft, the shadow rapidly approaching the aircraft from behind before totality and receding ahead of it after totality. The symmetrical shape of the corona and the great length of the equatorial streamers were very noticeable. The remarkable colour effects in the sky and on the clouds were most impressive.

Mr. H. W. Newton saw the eclipse in similar conditions from a B.O.A.C. aircraft.

Several members of the staff joined the expedition, organized by the Royal Astronomical Society and the British Astronomical Association, to observe this eclipse. Dr. J. G. Porter gave a broadcast commentary for the B.B.C. during the eclipse.

... For the convenience of observers of the total solar eclipse of 1954 June 30, special time signals were transmitted between 0900 and 1500 by the Post Office long-wave transmitter at Rugby and by associated short-wave transmitters. In order that the signals might serve also for a programme of radio observations, the seconds dots were lengthened from the normal duration of 0.1 second to become dashes 0.3 second in length. On the ten days preceding the eclipse, rehearsal time signals were transmitted between 0945 and 1030. In view of the difficulty experienced in obtaining reliable measurements at Abinger of the Rugby short-wave transmissions, the co-operation of. the Fernmeldetechnisches Zentralamt. at Darmstadt and of the Geodätisches Institut at Potsdam was invited. Results obtained at Abinger, Darmstadt and Potsdam have been described and tabulated in a departmental report. The assistance of the two German establishments is gratefully acknowledged.

... Much work was done in the supply of special data in connection with the total solar eclipse of 1954 June 30; a leaflet describing the eclipse as visible from the British Isles, was prepared for sale to the public.'

The report of the special correspondent of The Times travelling on the same plane as the Astronomer Royal

The text below was written on the day of the eclipse and is taken from the following day's edition of the The Times (1 July 1954) which also carried two images of the eclipse and a map showing the path of totality.

'A total eclipse in all its splendour was seen from the air to-day by the Astronomer Royal, Sir Harold Spencer Jones, F.R.S., and a small party of scientists and others flying in a R.A.F. Hastings aircraft off Iceland. We had been taken to this remote area because the track of totality between Greenland and Iceland passes through the zone in which aurorae are most frequently seen and it was hoped that their daytime existence might have been confirmed. But no sightings of aurorae were made. While the moon's shadow, which first touched the earth in Nebraska in the United States, was crossing the Atlantic Ocean at about 1,700 miles an hour this Hastings aircraft, at a more leisurely 236 miles an hour, was being placed in the centre of the 70-milewide track. At a height of 8,500ft. there was a clear sky above; but clouds below, like masses of cotton wool, reached to distant horizons.

It was not until about three-quarters of the sun's face had been covered that light began to fade rapidly. The snowy-white clouds changed quickly to deep blue and a few moments before totality the western horizon, was a brilliant orange colour merging through pale green to the blue-black sky above.

The eclipse as seen by the Astronomer Royal. From the 10 July edition of The Illustrated London News

All the wonder of an eclipse was visible. The black face of the obscuring moon was encircled by a brilliant silver ring – the inner corona – beyond which extended a pearly white glow with long equatorial streamers reaching out to about four times the sun's diameter on either side. The duration of the eclipse in this particular area was two minutes 27 seconds, but as the aircraft was, during this period, also travelling eastwards we had an extra 22 seconds of unforgettable experience. A team of four associated with Edinburgh University had the double job of watching for a daytime aurorae and estimating the colour and intensity variations of scattered sky light during the period of totality. For these occupations their eyes were turned to the north and the eclipse was behind them … The Hastings aircraft which carried the Astronomer Royal and his party on a round flight of 2,100 miles is normally used by the R.A.F. Flying College at Manby, Lincolnshire. for specialist navigational training. On this occasion it was fitted with a "colorimeter," a device with red, blue. and green light filters which can be adjusted to provide visual colour matching with the sky. Details of colour and intensity of the sky light at 40deg. of elevation from the horizon during the eclipse period were transmitted by radio from the aircraft to one of the British teams in Sweden, where similar equipment is installed.

Sir Harold Spencer Jones does not think there is likely to be much scope for scientific work in the air on solar phenomena. He explained that most of the research work required apparatus which is absolutely steady and at a fixed position on the earth's surface; but its usefulness always depended on favourable weather.'

Eric Croppers account of the flight in the Hastings aircraft

In his book Back bearings: a navigators tale (2010), Eric Cropper fills in some of the details about the flight in the Hastings that are missing from other accounts. As well as organising the flight, Cropper was also one of the passengers on board. The pilot was Wing Commander W.J. Burnett.

Cropper tells us that the flight itself took nine hours in total and that whilst some people were setting up equipment and others slept, the Astronomer Royal was seen to reading an expurgated copy of Lady Chatterley's lover. Cropper himself ended up assisting Bennett McInnes with some of the auroral observations and reports that although the scientists were disappointed that had not seen any aurorae, they thought nonetheless that they had made some useful measurements.

Published papers by Observatory staff

The symmetry of the corona of 1954 June 30. Tommy Gold, MNRAS, Vol. 115, p.340

Further reading

Total Solar Eclipse of June 30: British Expeditions' Results. Roderick Redman,

Nature Vol.174, pp.247–249 (1954).

© 2014 – 2025 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan