…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

Recollections from 1956–1982

| Date: | 1956–1982 |

| Author: | Stuart Malin |

| Title: | In Remembrance of me |

| About: | The text below consists of edited extracts from Malin's unpublished work In Remembrance of Me, a copy of which has been deposited at the British Library. Malin's connection with the Observatory began in 1956 when he attended his first Summer School at Herstmonceux. Appointed to the staff in 1958, Malin started work in the Magnetic Department. He then spent two years at the Radcliffe Observatory in South Africa before returning to his former department at Herstmonceux in 1965. By then, control of the Herstmonceux site had moved from the Admiralty to the newly formed Science Research Council. However, as part of the transfer, although still based at Herstmonceux, the Magnetic Department was administered not by the Science Research Council (SRC) but by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC). Malin remained at Herstmonceux until 1976 when the department was moved to Scotland. He remained in Scotland until 1982 when he resigned to take up the post of Head of Astronomy and Navigation at the National Maritime Museum where he was based on the Observatory site. |

| Images: | 10 |

| |

|

| Copyright: | Text & images © Stuart Malin, 2024 |

Vacation Courses at Herstmonceux Castle, 1956–1958

© Stuart Malin, 2024

When a notice appeared on the KCL Physics Department notice board inviting applications for a summer vacation course at the Royal Greenwich Observatory, Herstmonceux Castle, I decided to go for it.

This was the first summer (1956) after Dr (later Sir) Richard Woolley had become Astronomer Royal and had moved from Canberra to take over the RGO at Herstmonceux. On arrival at London Airport he was asked by reporters what he thought about space travel. Possibly through jet-lag or more likely because he was hopeless at public relations, he replied “Utter bilge”, a remark that was to plague him for the rest of his life. A couple of years later, after the first artificial satellite had been launched, he was asked if he would care to revise his opinion on space travel. To his discredit, he gave the thoroughly pathetic answer “It depends what you mean by utter bilge.”

But he did get some things right, one of which was the institution of summer vacation courses for undergraduates as a way of introducing them to the world of professional astronomy. The scheme was to bear an abundance of fruit. There are very few leading British astronomers who did not get drawn to their careers by attending one of the courses.

The first one was rather slim and took place before the post-war move to Herstmonceux was complete and there were few facilities or telescopes. I received a travel warrant and was met at Pevensey Bay Halt (made famous by Spike Milligan, who was stationed in nearby Bexhill during the war, as “the last outpost of British Railways”) and taken to the castle to join about five other students. We were accommodated in attic bedrooms in the castle and could buy lunch in the staff canteen, but there were no arrangements for an evening meal other than to give us the use of the kitchen. There was a morning and evening mini-bus run to the village to ferry staff to and from work, and we could hitch a lift to get provisions from the village shops. None of us had much idea about cooking – me least of all – but somehow we managed. I remember potatoes featuring prominently on the menu. These we peeled in a machine that was designed for sack-loads of potatoes rather than the few we used. This made timing quite critical – the interval between them being not properly peeled and reduced to tiny marbles was only a few microseconds. Similarly with the heavy-duty masher that would spread our humble ration of potato as a wafer-thin inside coating to the enormous caldron, with about ten percent fired out of the top. I don’t know what Mrs Marples, the Canteen Manageress (and much later Lady Woolley, but that is another story), thought of our abuse of her kitchen, and much admire her restraint in not telling us.

Each student was assigned either to a department or to an individual astronomer. I was given to Bernard Pagel – I hope he was grateful. My task was the measurement of radial velocities from the spectra of stars on photographic plates, which I found to be rather exciting. I don’t know where the spectra had come from – certainly not Herstmonceux as there were no suitable telescopes there at the time. On either side of the star spectrum there was a spectrum of iron from a source at the telescope, and therefore stationary. The spectral lines from the star were displaced slightly relative to the corresponding iron lines because of the Döppler effect and this displacement was measured for a number of lines using a screw micrometer attached to a microscope. The mean displacement could then readily be converted into radial (i.e. line-of-sight) velocity. I was not very fast nor, I suspect, very accurate, but I threw myself into it with a will.

After lunch on most days we would be given a lecture in the chapel. Bernard Pagel and Olin Eggen bore the brunt of the lecturing, but others were given by various department heads and by the AR (the full title of Astronomer Royal was seldom used). It was a privilege to be lectured to by such an august astronomical company, but straight after lunch was not the best time and, probably along with most of the others, I would doze off as soon as the first slide came up and the lights went down – a practice I have continued to this day, though with steadily decreasing feelings of guilt. The late nights we kept did not help. I would like to say that they were spent in looking at the stars, but that would not be true, not least because, despite being one of the sunniest sites in England, the Sussex nights were not special and only one in four, on average, was clear.

The evenings, after the nightly saga in the kitchen, were our own, except for Wednesday night, when country dancing in the ballroom was more-or-less compulsory. This, together with playing Bach fugues on the piano, was one of the AR’s fetishes and no astronomer with any ambition would dream of being absent. Besides, it was quite good fun and one of the few chances to get to grips with the host of young lady scientific assistants that the AR had collected. This was before the introduction of electronic computers and nearly all of the heavy routine calculations were done by school-leavers with a few A-levels. The AR must certainly be given credit for his ability to pick out pretty girls. When the country dancing was over, the girls were all loaded into the observatory bus and shuttled off to the station, while we lonesome bachelors wandered forlornly back to our attic. But at least the ice had been broken and we could follow up friendships the next day in the office, or after lunch in the extensive grounds.

Besides the beautifully restored Elizabethan castle (how many workplaces include a chapel and a ballroom?), the observatory had wonderful romantic gardens. When the observatory first moved there from London many of the staff were accommodated in wooden huts to the south of the castle – strictly segregated into men’s and women’s hostels, which were separated by a common room with table tennis and similar facilities. Being over a mile distant from the village, those who were not addicted to table tennis had to make their own entertainment in the evenings and this inevitably led to a steady stream of weddings. Whenever this happened there would be a staff collection for a wedding present followed by a presentation in the staircase hall, attended by all staff and made by the AR. He was primed by somebody with the basic data about the couple, but always started proceedings by announcing the forthcoming union as though it had been a newly discovered comet: e.g. 1956f, for the sixth wedding of that year. These were embarrassing occasions both for the couple and for the AR, but tradition had to be maintained. When my own turn came in 1963 Irene and I were lucky as the AR was abroad and the presentation was made by his Chief Assistant, Dr Hunter, who was much better at such things.

I had greatly enjoyed the first student course and signed up as soon as possible for the next one the following summer. This was much larger and rather better organised than the first one, with a bus to take us out to The Chestnut Tree, a local restaurant, for our evening meal. During one such meal, there was a sudden lull in the conversation and from the radio in the kitchen came the words “… enjoying the advantages of mains drainage”, an expression that has stuck with me ever since. There were also girls on the course (as there were on the second course of the first year, but I was unaware of this at the time), but they were, with one exception, no competition for those provided by the observatory. The exception was Charlie Sheffield’s girlfriend. They had both managed to come on the course and treated it as a government-funded honeymoon in the most delightful of settings.

But Charlie at least did work during the day. He and I were assigned to Eggen that year and shared a large office with John Alexander, who had just joined the permanent staff. Charlie was a crossword maniac and was never happier than when he was worrying away at an anagram (except possibly at night). We got involved in discussing the viability of hot-air balloons – this was long before the modern propane-powered ones had appeared on the scene – and undertook calculations involving mass, temperature-gradient, conductivity and so on. But the results could only be verified by an experiment. I recalled a Boys’ Own Paper article about making one from gores of tissue paper with a meths-soaked wad of cotton wool wired on at the bottom. This we constructed and it worked quite well, even narrowly failing to set fire to the room in which we tested it. But Charlie wanted something on a bigger scale.

He came into the office one day, after a trip to Eastbourne, with most of the contents of a model-making shop – balsa wood, tissue paper and dope. (The sort of dope used for tightening tissue paper on balsa frames, I should clarify.) Astronomy was abandoned as we designed and constructed possibly the largest hot air balloon since that of the Montgolfiers, standing some ten feet high. After our lucky escape with the pilot version, it was clear that this was to be an outdoor balloon. The launch had to be suitably marked, so we (“we” by now included most of the students and a few of the staff) arranged for a party to which all the girls and selected others were to be invited. We obtained the firkin of Merrydown as well as other booze, with the aid of Arthur Milsom and Harry Cook, whose peaceful bachelor flat in the castle attic we students seasonally invaded. The balloon was suitably decorated with its name “EGGEN” (for Extra-Galactic Geophysical Experimental Nephoscope) on one side and “Mars or bust” on the other. It later emerged that many of the girls rightly feared for their modesty if the EGGEN failed to reach Mars.

Ideally we should have waited for a less breezy night, but we had little choice, so at dusk the launch went ahead. With four stalwart(ish) students to hold it in place, the pre-heating pie-dish of meths was set alight and, after it was thought to have done its job, the smaller dish of cotton wool and meths that was to fly with EGGEN and provide a bit of weight at the bottom for stability was installed. This was then lit and the students released their hold. Whether they failed to release simultaneously, whether there was a skittish gust of wind, or whether there was a design fault is not clear, but the device rose swiftly into the air and then turned on its side, allowing the flame from the burner to catch the fabric. However, it continued to rise, blazing impressively, to well above the height of the castle before plunging spectacularly into the moat. This is all recorded on black-and-white photographs somewhere. The experiment was deemed a resounding success, and we all repaired to the attic for the party. That, too, was a success, but, as ever, the young ladies were whisked away by the observatory bus before any serious harm could be done. The castle residents finished off the liquor and went to bed. Only in my case at least the night didn’t end there, as detailed earlier.

This event set the pattern, and successive student groups (there were two sessions each summer) were expected to do something outlandish, such as the Great Telephone Plot of the following year. Before proceeding to the following year, however – I was greedy enough to come three years in succession – there are a few more events of the second year to record. The most important of these was my first proper girlfriend, Linda Mather. She had joined the staff from school after taking her A-levels, as was the pattern for scientific assistants. She was assigned to the AR’s department and shared the office with John Alexander (whom she later married), Charlie and me. The boy-friend/girl-friend relationship ran its course over the next couple of years and then faded out, but we remained – and still remain – friends.

Other notable friends made on the second course were Gordon Walker and Terry Deeming. We all hit it off very well and agreed to meet up again at Herstmonceux the following year, which we did. Terry was extremely talented and could easily have pursued a musical career rather than an astronomical one. To give some idea, he played the piano part of César Franck’s Sonata for Violin and Piano at a concert one year. As a result he decided that the violin was a more useful instrument than a piano for social music-making, as well as being more portable, so he took it up. The next year he performed the same piece at a public concert, but this time playing the violin part. He was a student at Birmingham University, where Professor Zdenek Kopal was the leading astronomical light. Kopal used to show visitors the department’s rather small telescope and describe it as “the largest telescope of its size in the World!” Gordon was a Scot and proud of it. He could quote long passages from Robert Burns and did so frequently. We used to spend the evenings together playing table tennis, eating Wagon-wheels and gathered around Terry while he performed on the piano. Both Terry and Gordon went on to become successful professional astronomers, Terry in Texas (where he died young) and Gordon in Canada, where he pioneered the discovery of planets orbiting nearby stars.

For my third Herstmonceux vacation course (what indulgence), I was working with the AR. While it was a privilege to work with such an eminent scientist it was also rather daunting as, despite his best efforts, he was never an easy man to get on with. Once again we were measuring spectral lines with a screw micrometer, this time from coudé plates obtained at Mount Wilson. One of us would look through the microscope and bisect the line while the other would read the micrometer and record the result. We took turns at each job. Linda was also part of the team.

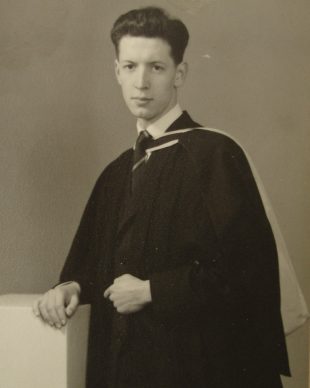

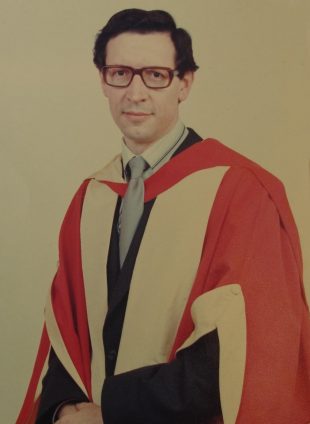

Herstmonceux – bachelor days, 1958-1963

My student days at King’s had finished, but I was in a sort of limbo as I couldn’t apply for a proper job until the examination results came out. So I indulged myself with a third vacation course at Herstmonceux. Not an entirely mad idea, as it was more than likely that I would eventually work there and it did no harm to get my feet under the table. When the results came through, they were not good enough for me to take up a PhD place at London University. So, on the Astronomer Royal’s advice, I applied to the Civil Service Commission for a place at Herstmonceux. The AR assured me that three years at Herstmonceux would be every bit as good as a PhD as far as career prospects went, and this proved to be true as those who entered three years later having completed a PhD came in at the same grade as mine. This remained true so long as I was at the Royal Greenwich Observatory (RGO), but a PhD would be a major asset if I wanted to work elsewhere, which is why I eventually got around to doing one.The Civil Service were not the fastest of movers and the vacation course had finished before I had been called to interview. Finances were running low, so I went to work at the only factory in Wycombe that always had vacancies – Jackson’s Millboard and Fibre. The made large boards out of a papier mâché-type mulch for later use as door linings and suchlike in the motor industry. They worked three eight-hour shifts: 10 pm to 6 am, 6 to 2 pm and 2 to 10. After a week, one missed a shift and joined the next one. Some workers opted to do a shift-and-a-half to earn more money, and a few workers even did a shift-and-a-half, twelve hours on the trot, every day. One shift was more than enough for me. I started as sweeper-upper, being trained in this art by the foreman who explained the use of short, low sweeps to avoid raising the dust and the judicious use of water. I hadn’t realised how technical sweeping was. Or how physically demanding it was to keep it up hour after hour.

I soon progressed to the ovens, hanging the wet soggy boards onto a moving overhead chain as they entered the oven and unhooking them, lighter and firmer, but too hot to handle without gloves, as they came out. The rate of work was dictated by the speed of the chain, over which we had no control. The work was done by a team, two men hanging and two un-hanging and stacking. I was a welcome member of a team, not because of my less-than-muscular physique, but because I was able and happy to count up to fifty, after which number a different coloured board had to be inserted – a task that many of the others found beyond them. The work was adequately paid and kept my Austin seven in petrol, which was just as well, as public transport was not available for the times of some of the shifts. I suppose I could have cycled there, but I am not sure that I would have had the strength to cycle back. It was an interesting insight into a world that was completely new to me, but not one that I could have faced entering for more than a few weeks.

Eventually, to my great relief, I had the Civil Service interview (at a venue in London, but with a couple of familiar, if rather senior, Herstmonceux faces on the other side of the table). I was nervous and gave some rather silly answers to questions that I really knew the answers to perfectly well, but no opportunity to correct. I was relieved, therefore, to be offered the post of Assistant Experimental Officer a week or so later. It would have been better, but not very likely, to have been offered Scientific officer, as my mate Derek Jones was, but he had a very good degree from Cambridge and was a couple of years older than I was, having done his National Service in the Royal Air Force. I had deferred my National Service as was permissible during full-time study, but it was still hanging over my head.

Government Science jobs were divided at the time into three grades: (1) Assistant grade, comprising Scientific Assistants and Senior Assistants. Scientific Assistant was the entry level on leaving school, usually with good O-levels or a few A-levels. Promotion to Senior Assistant was very rare and only for those with many years of service who had not obtained qualifications to progress to the next grade. (2) Experimental grade, going from Assistant Experimental Officer (AEO – me) to Experimental Officer (EO) to Senior EO and, rarely, to Principal EO. Entry was at degree level. Experimental pay and promotion prospects were good, but the work was defined by others and lacked the prestige of (3) the Scientific grade, for which entry required a very good first degree or, more commonly, a higher degree. The range went through SO, SSO, PSO, SPSO, DC(Deputy Chief)SO, CSO (e.g. the AR), God. These were the ones who initiated research. PSO was the grade of a Head of Department, which seemed incredibly elevated to me until Derek Jones said that, so long as we kept our noses clean, we had a good chance of ending up at that level. As, indeed, he did.

So I hung up my Jackson’s broom (using the hanging-up skills I had acquired there), packed my worldly goods into my trusty Austin seven, said goodbye to my mother and Wycombe friends, and set out for a new life in Sussex. I had been invited by the other incumbents – Arthur Milsom and Rodney Jackson – to move into the bachelor attic of Herstmonceux Castle with them, even before the AR suggested it, so that is what I did. Bob Dickens, later my best man, had just got married and moved out, so their numbers needed reinforcing. Derek Jones, also a new recruit, moved in just before me. Arthur, an EO and the oldest inhabitant, was mother superior. He managed the rest of us and did all the cooking (brilliantly) with the rest of us as skivvies. It worked very well and I don’t recall any bickering. Rodney worked in the Chronometer Workshop, which reported directly to the Navy. Derek was an SO and I was an AEO.

The first working day I reported to the AR for assignment to a department. I had notions of joining the Astrophysics Department and solving the problems of the universe: where we have come from and where we are going to, that sort of thing. But he told me “I am going to assign you to the Magnetic Department.” I suppose it could have been worse. It might have been the Nautical Almanac Office (NAO), where Bob Dickens worked, but the Magnetic and Meteorological Department, or Mag & Met as it was known, was not much better.

The PSO in charge of the department was Herbert Finch and his number two was Dick Leaton (SSO). More of them later. Then there was George Wells (SEO), the chief meteorologist, a lovely man who was nearing retirement. One of his favourite sayings, though he did not practice it, was “I burn my candle at both ends, it will not last the night. But oh my foes and oh my friends, it gives a lovely light.” He was an avuncular figure and all the girls with whom he shared the observatory transport to and from Pevensey Bay Halt made a great fuss of him. He confessed that, as he got older, the girls he was attracted to got younger, and as he approached sixty his tastes were getting perilously close to the age of consent. But it was all talk – the only transactions that occurred were for George to lend them money when they got short towards the end of the month.

As well as measuring the weather, George was also a good indicator of it. Shortly before ten each morning, he would set out on the quarter-mile walk to the Met Enclosure, never wearing a coat. But if the temperature was well below freezing, he would weaken so far as to carry one. Everyone, from highest to lowest, knew him as George, except Finch, on whose desk resided the sole outside-line ’phone. When someone rang and asked for George, Finch would take a few seconds to realise who was wanted, then call across the office “Wells: telephone.” They had been colleagues for only about twenty years! But the old school was like that – just surnames. All letters sent out were deemed to be from the Astronomer Royal, no matter who had written them. To Woolley’s credit, things became a little more relaxed under his AR-ship, but he was still austere and remote, partly due, I suspect, to shyness. He said on one radio interview that he had a mental green baize door, on one side of which were the staff he knew and on the other side were the others. This did not go down at all well with the staff, who were well aware how few were on the “known” side.

But I was talking about the Mag & Met staff. Peter Standen sat opposite me at a desk that abutted mine. He had started work just a day earlier than me as a Scientific Assistant working with George Wells. That day was very important, as it meant that he had met the Duke of Edinburgh when he came to open the Equatorial Group of telescopes, while I did not. I made up for it later, though. Peter was an excellent athlete. At the time he was the English 400 and 800 meter junior champion. He spent most of his spare time training, and chided me for taking too little exercise. However, I claimed that I was fitter than him for what really mattered. I could sit at the desk for hours, whereas he had to get up and move around every few minutes. Also he was off work with colds or injuries far more often than I was. On one occasion he challenged me to a race round the cricket pitch (about 400 metres) – twice round for him and once for me. To my shame, he beat me.

For a short time I overlapped with Bob Lorton, who was a Scientific Assistant, but acted as though he was head of the department. He was good company in spite of his airs (inherited from his “county” mother) and introduced me to italic script. My writing, never good, had become illegible even to me after three years of note scribbling, so it was time to do something about it. Bob took me in hand and taught me from scratch. I can still do it beautifully if I take my time, and use it for writing invitations and entries in the St Margaret’s Book of Remembrance. Bob is remembered for turning out for an observatory cricket match dressed in immaculate whites, while everyone else just wore casuals, and then proving to be totally incompetent with both bat and ball. He wasn’t a lot of use at his work either.

The final staff member at Herstmonceux (there were others at the Hartland Magnetic Observatory – a field-station in North Devon) was Stella Francis, another Scientific Assistant, who was both scatty and charming. She and Peter, together with Brenda Denman of the Solar Department, which shared the same large room, undertook the important task of tea-making.

Much of the work of the Mag & Met was of a routine nature – making regular magnetic and meteorological observations and preparing them for publication – but every five years there was the more interesting job of preparing magnetic navigation world charts for the Admiralty. These charts had a long and distinguished history, the first having been prepared and published by Edmond Halley (the second AR of comet fame) in 1700. A new set was required for 1960 and that was the main reason for assigning me to the department. The task involved updating the 1950 charts using the best estimate of secular change over the interval 1950-1960 deduced from worldwide magnetic observatory data, and correcting the charts using post-1950 observations.

While working on the charts (there were five sectional charts as well as the World one), our American colleagues who produce a rival (but inferior) set of charts, sent us several boxes of computer print-out tabulating all the data they had collected from land, sea and air surveys around the world. I am not sure if this was meant to be helpful or to slow us down. There was a huge body of data to go through, and ultimately it did not add a lot to what we already had, but it was a kind gesture and the start for me of friendships that continued until after their and my retirement. Kendall Svendsen was a particular mate.

For remote parts of the world where no observations had been made, it was possible to do some rather refined interpolation using spherical harmonic analysis. Dick Leaton chose to chuck me in at the deep end, giving me the fearsome spherical harmonic equations and coefficients, and leaving me to get on with it. I was the first member of the department to have had a full-time university education – both Finch and Leaton had got their BSc’s externally, after many years of night-classes – and I suspect that I was being subjected to a sort of ordeal by fire. It was difficult, but I was not going to be beaten and, rather to their surprise, I think, I managed to sort it out and successfully make the calculations. Finch and Leaton had only recently managed to make a spherical harmonic analysis, following the example of Spencer Jones (the previous AR) and Melotte. After my struggles I was admitted to the club. A difficult, but useful introduction as I later went on to become an authority on the subject.

Although I applied myself conscientiously to the magnetic work, I was still a frustrated astronomer. The astronomical departments did not have enough staff to man all the telescopes, so people from other departments were encouraged to join in the observing. This suited me very well, and I became a regular observer on the 13-inch Astrographic refracting telescope (telescope sizes are specified by their diameter, which is a measure of their light-gathering power), the 26-inch photographic refractor and the largest telescope at Herstmonceux, the 36-inch Yapp reflector. Observing schedules were distributed a week in advance, specifying date, telescope and evening or morning session. The observer got paid 5/- (I think) and was given a half day off for each observing session, whether cloudy or clear. Unlike in Airy’s day (he was the Astronomer Royal from 1835-1881), the observer was not required to stand by the telescope if it was cloudy or raining, but was expected to keep an eye on the sky and leap into action if it cleared.

Much as I enjoyed observing, I did not enjoy getting up for the morning sessions. I would go to bed early and set the alarm. When it went off, I would first listen to see if I could hear rain; if so, I set the alarm clock for an hour later, turned over and tried to go back to sleep. If not, I had to stagger to the window, open it and look up, hoping for cloud. The sight of stars produced a sinking feeling followed by a brief bout of conscience-wrestling during which I wondered if anyone would notice if I didn’t turn up. Then I would get dressed and turn out. Once I had got to the telescope, all was well, unless it had clouded up in the meantime, which could be very annoying.

The small hours of the morning are not the best time for rational thought, so, as far as possible, one avoids thinking at the telescope. Though there is some scope for changing things in the light of observing conditions, as far as possible the observing programme is planned before going on duty. This plan is then worked through and the results recorded photographically (except for double-star observing, which is still done by eye) to be studied in detail during normal working hours. Nowadays, of course, electronic recording has taken over from photographic, but the principle is the same.

My favourite telescope was the 26-inch refractor, which was used for determining the distance of a star. From the different viewpoints of opposite sides of the Earth’s orbit, a fairly nearby star would appear to change its position very slightly relative to the distant background stars. This change of position (“parallax”) was measured by comparing photographic plates taken nearly six months apart. The difficulty is that, if you photograph a star when it is high in the sky at around midnight, six months later it will be high in the sky at around mid-day! To overcome this problem, one photograph is taken just after dusk and the next, six months later, just before dawn. So the telescope was used intensively around dusk and dawn. To make the best use of these few precious hours, observing was sped up by having a rising floor that enabled the sharp end of the telescope to be reached easily and quickly. The floor was made by the Wurlitzer Company, which was more famous for making the cinema organs that would rise through the floor for inter-film entertainment.

It was fun to ride on the rising floor, which was so smooth that it appeared to be the telescope that was sinking rather than the floor rising. But it could be nausea-inducing if the dome was rotating at the same time. Guiding the telescope during an exposure was done from a standing position, but, for a star near the zenith, this was a bit of a strain on the neck, so I got into the habit of laying on the floor with my head on a pillow and using the floor slow-motion to bring my eye to the eyepiece. Until one day during maintenance the up-button stuck and the floor continued to rise, bashing into the telescope and doing quite a bit of damage. After that I put up with a strained neck.

Observing was not usually scheduled for the weekend, but, because I lived on site, I was sometimes scheduled for the 36-inch on a Saturday or Sunday. One Saturday the evening was very cloudy so Rodney and I decided to go to the cinema in Eastbourne. There was nothing of any particular interest available, so we settled for a film about the un-dead. It was so terribly made that it was enjoyable and we laughed all the way through. When we got back to the Castle, the sky had cleared, so Rodney went off to bed and I went to the telescope. I was alone in the Equatorial Group, working in darkness, and suddenly the un-dead did not seem quite so funny. It was one of those “Oh God, get me through to dawn and I will worship you forever” moments. He kept his side of the bargain, but I didn’t keep mine.

Another such moment occurred shortly after I had been with Kathryn to visit her grandmother in darkest Herefordshire. There was an ancient ruined church in a field nearby and the grandmother told us of recent goings on there that involved men wearing antlers, until the police broke it up. Alone in the Equatorial Group again, I imagined stag-horned men lurking in every shadow. I don’t know why the horns held me in such thrall, but they did. I turned up the dim red floor lights as much as I dared and chose to photograph the spectra of the faintest available stars, so that I would not have to leave the dome to go to the darkroom for a new photographic plate, and eventually dawn came to my rescue.

The castle itself was not a spooky place, but it did have its quota of ghosts. One of these was said to be a 7-foot headless drummer who would walk the battlements beating his drum on moonlit nights. How does one measure the height of a headless person? I believe he was a 6-foot headed person who pulled up his jacket to the top of his head to appear both headless and 7-feet tall. Why should he do this? Sussex was a notorious smuggling county and Herstmonceux Castle was close to the Pevensey coast with high tide at about midnight when there was a full moon. What better warning to the locals to keep their heads down as “the gentlemen came by”?

The other ghost was the Grey Lady. To collate the various stories about her, she was believed to be the wife of one of the early Lords Dacre whom he had bricked up alive in the castle walls. She would variously appear on her own near the Church, or with a donkey in the grounds, but always wearing a grey shift. Danny Elliott, the observatory stonemason, had a workshop near the West Gate, just by the Church. He had been working late to finish carving a commemorative stone that was to go in the newly-constructed clubhouse. He packed up about midnight and set off for home on his motorbike, with a necessary pause to open, get through, and close the gate. Just as he was about to continue on his way, a woman dressed in grey came from the direction of the church and started to cross the road in front of him. Danny waited for her to cross, but, as soon as she got into his headlights, she disappeared. Danny smartly let in his clutch and also disappeared – down the lane to his home. Next day he had the dilemma of whether to keep quiet about it, or whether to risk ridicule by telling. Obviously he chose the latter option, or I wouldn’t have been able to write this. He was not a drinker, nor given to hoaxes or flights of fancy. Just an honest craftsman who felt that the truth should be told and let the consequences take care of themselves.

One night Arthur, Derek, Rodney and I were sitting in the castle drinking Arthur’s excellent home-made hooch and talking about this and other older and less well documented appearances of the Grey Lady when we realised that it was nearly midnight and there was a full moon. So off we traipsed towards the church on a ghost hunt. We were all taking it suitably seriously except Rodney who, possibly as a result of Arthur’s brew, kept capering ahead and jumping out on us from behind bushes. I don’t know if this frightened her off, but we got to the church without any sighting of the lady. The church was unlocked (as was the practice in those days) so we went in, climbed the ladder to the belfry, and waited. At about 2 am we called it a night and went to bed.

But we hadn’t quite finished with ghosts. Each summer our peaceful bachelor flat was invaded by the vacation students. Both Derek and I had been vacation students ourselves, so were reasonably tolerant of them, but that did not prevent us from preparing a “welcome” in the form of a haunting. Arthur prepared a tape recording of ticking clock and rattling chains which, when played at half speed, was suitably spooky. Derek reckoned that he could gibber convincingly, Rodney had plans (never realised!) of wearing a sheet and walking up and down the bedroom corridor a couple of feet above the ground. My contribution was a rubber glove filled with water and on a string so that it could be lowered from the roof to paw at the bedroom windows. To help set the atmosphere, bits of cardboard were inserted into the socket of the main bedroom light so that it wouldn’t switch on. Obviously it wouldn’t be possible to haunt all the students, so we looked at the labels that had been stuck on the doors and selected “Yallop” as the most promising candidate. A speaker was installed above the ceiling for Arthur’s sound effects and the night that Yallop moved in we gave him the works. We couldn’t have picked a worse target. Over breakfast the next morning, we asked him if he had heard anything during the night. “Only a few fools making silly noises in the corridor.”

Despite a full work and observing regime, there was still plenty of time for social life and for relaxation. I rediscovered the delight of reading novels, rather than textbooks, without a feeling of guilt. I regularly bought a new Penguin each week. I had brought my radiogram from Wycombe and enjoyed lying on the bed reading a book and listening to classical records. The two pursuits got entangled: for example, I cannot hear Cesar Franck’s Symphonic Variations without thinking of John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, and vice versa. And I was beginning to get over my gawkishness with girls. There was a large pool of eligible young ladies at Herstmonceux and after Linda and I had wound up our relationship, I enthusiastically plunged in.

My flatmate Rodney was a source of great wisdom when it came to Going Out With Girls. Before a date, he would prime me on what I should and should not do. Then when I got back to the flat after a date, there would be a de-briefing (if you will pardon the expression), after which Rodney would advise me on how far I should go next time. It worked like a dream and it was only many years later that I found that Rodney’s experience of girls was even less than mine. It was all theory.

It was about this time that Granny Malin died, aged ninety four, which was a really great age in those days. She had never been the most loveable of old ladies, but I dutifully gave up a visit to the Lewes bonfire celebrations to attend her funeral. I was amply rewarded with an inheritance of £50, but I didn’t let it change my lifestyle! The house and what was left of the money quite properly went to Aunt Dorothy, but it was a pretty poor reward for having given up any chance of a life. Dorothy told me that she would have liked to learn to drive and also to visit New Zealand, but by the time her mother died she was an invalid and could not even go upstairs.

After the 1960 charts had been finished, it seemed like a good idea for me to go down to Hartland and learn at first hand how to make magnetic measurements. I have since visited many magnetic observatories and become something of an authority on them through direct involvement, using their data and studying their history. But Hartland was my first. It is a top-quality observatory, so I couldn’t have done better. The man in charge was Percy Rickerby (SEO) and his staff were Peter Wilmoth (EO) and an odd-job man and his wife. Running such an observatory requires meticulous attention to detail, but is essentially repetitious and very boring. It calls for a particular frame of mind that I don’t have.

Nevertheless, it was interesting to spend a few weeks learning the routine. I stayed in Mrs Evans’ B & B in a room with a view of Lundy Island. That was when I developed a yen to go there which was not satisfied until many years later.

But I was writing about magnetic observatory routine. Before starting one must carefully remove anything magnetic from one’s person. (Sir Harold Spenser Jones, when Astronomer Royal, failed to remove the metal shoe inserts he wore for his fallen arches, and screwed up all the observations.) The first visit is to the variometers – photographic recorders in a heavily insulated and sealed-off chamber – to wind the clocks, check the light bulbs and change the recording paper. Then back to the dark room in the main office block to develop them. A cup of coffee, a check of the chronometer against the radio time signal, and off again to the Absolute Building to make some accurate spot observations which will be used to calibrate the photographic records (magnetograms). These observations called for great care and skill as we were aiming for an accuracy of one nano-Tesla, which is right on the limits of detection.

The afternoon is spent measuring up the magnetograms and preparing tables of hourly mean values for transmission to Herstmonceux, and for sorting out the innumerable things that needed to be sorted out. But enough of this, even I am finding it boring. Observing instruments and methods have moved on so far and so fast that the methods I first learnt are now only of historical interest.

Back at Herstmonceux I needed something to get my teeth into, so Finch and Leaton introduced me to a project that they had started many years before, but had failed to bring anywhere near to completion. This was the analysis of Greenwich and Abinger magnetic data for variations induced by the Sun and the Moon. Greenwich and Abinger were the magnetic observatories that had preceded Hartland, before interference from electric trains had rendered each in turn useless as an observing site. The lunar analysis, as it was known, had been proposed by Sydney Chapman, the Great Man of geomagnetism, who had briefly worked at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, as Chief Assistant to the Astronomer Royal before moving on to better things. He was very keen on lunar analysis and, besides doing several himself, was always encouraging others to do more with a view to producing something approaching a global coverage. The solar variations are quite large and can usually be seen just by looking a magnetogram. But the lunar variations are miniscule and can be detected only by analysing a vast number of observations. The first stage is to punch alternate magnetic hourly mean values onto 80-column Hollerith cards, one card per day, and that is as far as Finch and Leaton had got, with most of the work being done by an agency. Before I could take things any further, the punched records needed to be checked for accuracy, and then I was ready to start the analysis itself which involved a lot of serious computing. But first I needed to understand the Chapman-Miller method, which is what was going to be used. This was contained in a heavily mathematical paper whose senior author was – you’ve guessed it – Sydney Chapman. It was stretching my maths to breaking point, but, with help from Dick Leaton, who was no mean mathematician, we managed to crack it.

Understanding the method was one thing, but applying it was something else. It had been hoped that the RGO would have acquired an electronic computer by that time, but the Admiralty was not to be hurried, so we had to start the process using electro-mechanical devices: sorter, tabulator, collator, etc., that were housed in the Nautical Almanac Office. The great monsters that always used to appear in science fiction films before electronic computers came along. I have to call them “electronic computers” because the word “computer” on its own had quite a different meaning in those days. It applied to a young, usually female, Scientific Assistant whose job it was to do all the routine calculations that would later be done electronically, and to make the tea as well. But from now on I will drop the “electronic” and hope that the context is sufficient to distinguish between flesh and metal.

In anticipation of the installation of the new computer, it was planned to remove the electro-mechanical machines that, by now, had become essential to the first stage of the analysis. In a bid to beat the removal deadline, we used them 24 hours a day, Peter Standen taking the daytime shift and me working through the night. The work involved sorting the many thousands of punched cards into groups according to various criteria (season, lunar distance, magnetic activity, etc.) using the sorter, then forming group sums using the tabulator and punching out a further set of cards. The operator did not have to do much more than keep the feeds stacked with cards and unload them at the other end. Except when, as often happened, particularly after the cards had been read a few times, there was a jam. Then the machine had to be stopped quickly before the tangled mass of cardboard had reached unmanageable proportions, the torn bits of card removed, jig-sawed together and new copies made. Card-handling required a lot of minor skills that have now gone forever. Joggling the cards with the heel of the hand to make them into a tidy pack; fanning them so that they could be counted by flicking them past a thumb; holding them up to a light to confirm that they all had a five punched in column 38; pushing a shard back into a mis-punched hole as a temporary repair and so on. The biggest nightmare was to drop a pack of cards and have to sort them back into order. This could be done using many passes through the sorter, but if only a few hundred cards were involved, it was quicker by hand and avoided the high risk of a jam. The final operation was to use the backs of dead cards for shopping lists.

We completed the group sums before the deadline and it was planned to do the remainder of the analysis on the new computer, when it arrived. It was to be a mighty HEC4 (HEC standing for Hollerith Electronic Computer, the firm that was later to become International Computers and Tabulators and then International Computers Limited, Britain’s inadequate answer to IBM.) While it was awaited, a group of us was given lessons in how to program it by George Wilkins. One piece of homework was to write a recursive program to evaluate some function that could be defined by a series. Most students chose something useful like cosines or logarithms. I chose to program the Inverse Guddermanian. I am pretty sure my program was never used in anger, though it worked well enough. Even now I have no idea what the Inverse Guddermanian is used for.

Programming the HEC 4 was no simple task. Everything had to be written in binary (or bi-octal, but don’t let’s go into that) and punched onto a Hollerith card, twelve instructions to a card. Instructions were in very simple steps like “add the contents of register A to the contents of register B and store the result in register C”, or, even more simply, “shift the contents of register A into register A”, a do-nothing instruction that had to be inserted at various points in the program to avoid the computer getting indigestion. In code, this instruction was 39 ARA which was the number of a car I later acquired. Data were fed in on punched cards and stored in the 1024-word memory, which also had to accommodate the program. No, I have not dropped a “mega”; the total storage really was just over a thousand words. It was on a rotating drum and programs could be significantly sped up by choosing to return a result to a location two round from whence it came. Output was either on punched cards or on fanfold paper from a line printer – the characters for a whole line were selected by raising a separate line of type for each space to the appropriate level, then a bar would smack the lot against the paper through an inked ribbon with a most satisfying clatter. In this way a whole page could be printed in about a minute.

There was a wide range of noises available: the clunk of the printer, the grind of the card punch, the shlurp-shlurp of the card reader and an emergency bell. Though it was supposed to be for emergencies, it could be programmed in and I chose to use it far too often for the engineer’s comfort. I actually wrote a cha cha cha program by using all the noises rhythmically. The full-time engineer came with the computer and, as well as having a full day of the computer’s time each week for maintenance, he spent much of the remaining time changing diodes as they blew out. It was a rare event to get an uninterrupted hour of trouble-free computing out of the machine. The main part of it comprised banks and banks of glowing diodes, which produced so much heat that the computer had to have its own dedicated air conditioning, which occupied another room. But it was remarkable how much useful calculating we managed to get out of it.

The lunar analysis was finally finished, the results discussed (which was where Finch made his contribution), written up (largely by Leaton) and ready for publication. It would have been good to publish it in a respectable journal, but it was observatory policy at the time that everything should be published by HMSO in Royal Observatory Bulletins. This was intended to enhance the reputation of the RGO as an institution, but did not do a lot of good to the individual astronomers and was entirely unsuitable for geophysical publications. Nevertheless, we had quite a reasonable number of reprints which we sent to appropriate people. I still have a copy of a very complimentary letter that Sydney Chapman wrote on receipt of his copy

Computers were developing very rapidly and it was not long before the old HEC 4 was replaced with a serious machine. This was an ICL job (I forget the number) with spinning half-inch-wide magnetic tapes as favoured by the next generation of sci-fi films. It had a sensible amount of core store and, joy of joys, it supported FORTRAN, a high-level computer language that was half way to algebra. Another set of lessons was required, but I took to it like a duck to green peas, and soon became fluent. No more messing about with machine code and binary instructions. Not that I resented these. I learned to drive in a car with a crash gearbox, requiring double-declutching, which, I believe, made me a better driver. Similarly, I believe that learning the trade on the HEC 4 ultimately made me a better programmer. It was now possible to contemplate doing an entire spherical harmonic analysis by computer, without recourse to preliminary charting, and that is what I set about doing.

I was going to say something about Finch and Leaton, so will do so now. Herbert Frank Finch was a rather small man, a bit remote, but not unpleasant. He was an excellent pianist and a very good chess player. Unfortunately he was not much of a scientist, despite his part-time BSc degree (I don’t say part-time in any disparaging sense. Like the Open University degree, it is much harder to do it that way than full-time, when it is nearly impossible to fail). It was said that, when he did algebra, he would leave out all the plus and minus signs and add them later with a pepper pot. He had become Head of Department mainly by being in the right place at the right time – this happened during the war, when good staff were hard to come by. He has previously been in the Time Department. My first encounter with him was when I was a vacation student working with the AR in his office. He summoned Finch for some reason and when he knocked on the door, the AR invited him in, saying “Oh Finch. Wait a moment.” Woolley then continued to measure a photographic plate with me reading off the numbers while Finch stood Just inside the door for fully five minutes. What an incredibly rude thing to do to one of his Heads of Department, even if it had not been in the presence of a student. It was no wonder that when Finch received similar summonses after I had started to work in the department, he would come over all dithery, straighten his tie, pull up his socks and rush from the room. I am not sure if he went via the loo, but I suspect so. Another of his weak points was driving. Leaton used to tell the story of being driven by Finch (in his green Ford Popular) and saying, after a particularly near miss, “I don’t know how you missed that bus.” “What bus?” was the reply.

Brian Richard Leaton was always known as Dick (he used to answer the internal ’phone with “Magnetic, Dick”, to the great amusement of Ray Foord, among others). He resented having to work for Finch, from whom he did not attempt to hide his scorn, though Finch chose not to notice. The pepper-pot remark (above) came from Dick. Dick and I got on pretty well most of the time, though as I began to make a name for myself, Dick also got a bit resentful of me, but for the opposite reason. He had started work at Greenwich straight from school. He then got drafted into the Air Force during the war, during which time he travelled the world and studied for a degree. He also acquired a wife, Olive, who was a WAAF working with a searchlight battery. (No, not that sort of battery, they were powered by generators.) He had a great sense of humour and a huge fund of rather risqué stories which, with his background of amateur dramatics, he told with some panache. Dick was keen that the department should do some research as well as routine work, and it was he who got me started on writing research papers, some with him and some solo.

Having by now completed several major projects, I thought it was about time I made an attempt to transfer from Experimental to Scientific grade. Having convinced myself of the merits of my case, I applied for SO and got invited for interview in London, but I got steadily more apprehensive as the interview date approached. My flatmate Derek Jones (who had joined the observatory as an SO) took me in hand and gave me some coaching. During a walk along the sea front at Bexhill, he explained to me exactly how the interview panel worked. The chairman who sat at the centre was expert in nothing but interviewing. He would make the introductions and ask a few bland questions designed to put me at my ease. Then it would be the turn of the experts, who would press me with successively more difficult questions until they had established my limits. They were not vindictively trying to break me, just probing the depth of my knowledge. When asked a question that I could not answer, the technique would be to gaze into space while inwardly counting up to ten, and then say “I don’t know”. The pause was important, as it gave the impression that I was considering the question from every angle and probably knew more about it than they did, but modesty or discretion prevented me from divulging the answer.

We will never know if I would have got through the interview without Derek’s coaching, but it certainly put me into a much more confident frame of mind. I have used several of his helpful hints in later interviews, and been amused to see some of them used against me when I was on the interviewing side of the table. I think that, unlike Rodney and his amatory techniques, Derek was speaking from experience (gained in the RAF). Whatever the reason, as a result of that interview I became an SO.

Even after the promotion, the pay was still modest, so I continued to give Evening Institute lectures each winter. The pay for these was not special, either, but could be considerably enhanced if the Institute was sufficiently remote, as the mileage allowance was generous and tax-free. Gordon Taylor, a Senior Assistant in the Nautical Almanac Office, was said to make more from evening lectures than from his salary. He lectured at least three times a week and always a long way from Herstmonceux. There were several authorities who sponsored these lectures. My favourites (for purely financial reasons) were the Workers’ Educational Institute and the Oxford University Department of Extra-Mural Studies. Courses of twelve weeks could be managed solo, with a bit of cooperation from colleagues over swapping observing duties. They were all at it, so such swapping was part of the way of life. Twenty-four-week courses were rather more of a bind and best undertaken jointly. As well as spreading the load, this provided a regular swappee and halved the number of subjects one had to mug-up on. I shared a couple of courses with Bernard Yallop and others with Tommy Tucker, always amicably

As well as the money (always welcome) the courses gave valuable experience in preparing and delivering lectures. Also, the students got to be old friends by the end of a course and it was not unusual for one or more to have a “crush” on the lecturer – the glamour of even such petty authority! Of course, it would have been quite unprofessional to take advantage of this, but it was flattering.

The lectures would last for two hours, with a break for coffee. This would often involve a trip to an adjacent building when I would always hope for cloud. Otherwise, someone was bound to ask “What is that bright star?” My technique with such questions was to ask if anyone else knew the answer. When I had confirmed that they didn’t, I would assure them that it was Alcor, or some other randomly chosen name. If anyone did see through this ruse, they were too polite to confront me.

I am not sure exactly when, but sometime during my early years at Herstmonceux my deferment ran out and I was called for a medical preparatory to being called up for National Service. I was very pleased to fail the medical (asthma had its uses), so now I was free to pursue a career. I was also free to go out with girls, which I did enthusiastically. I mentioned earlier that there was a wide choice among the girls at Herstmonceux and I went out with quite a few of them – though not simultaneously. My longest-term girlfriend after Linda was Kathryn James, who I might easily have ended up married to except that neither of us was ready for such a commitment, so it faded out when she moved to London, though we carried on corresponding for a long time.

The most desirable of the observatory girls, Irene Saunders, was known to be off-limits, as she had a long-term boy friend with whom she had an “understanding”. That did not stop me pursuing her, however, eventually successfully.Irene and I spent more and more time together and it soon became clear to both of us that we were going to get married, though we didn’t get engaged formally until her twenty-first birthday. Being a romantic, Irene wanted a June wedding while I, for reasons of a £40 tax rebate, wanted to get married before the end of the financial year at the beginning of April. Like the hero I was, I had made the big gesture and agreed to sacrifice the tax rebate, but then fate intervened.

One day I got a telephone summons to the ARs office. As usual with the AR the entire message was “Come to my office”, with no clue, other than the voice, who was calling or what was the reason for the call. Finch-like I pulled up my socks, straightened my tie and went to the loo, wondering what misdemeanour I had committed. There were two people in the office and Woolley introduced the stranger to me as Dr Stoy, Her Majesty’s Astronomer at the Cape. He was looking for someone to replace George Harding as Cape Observer at the Radcliffe Observatory, Pretoria, South Africa. George was coming to the end of his three-year tour of duty there. I was surprised to learn that Woolley not only knew of my existence, but also that I was keen to get into astronomy, so this was my big chance. “Any questions?” “How soon do I have to decide?” “Dr Stoy leaves for South Africa in three days time. The longer you think about it, the less will be the time for the next man.” “When would I go?” “Middle of next April to allow a couple of weeks of overlap.” “But I was planning to get married in June.” “Then you will have to bring it forward.”

All of a flutter, I went straight from there to Irene’s office and broke the news to her. After the initial shock, she was as thrilled as I was. Next I had to ’phone my mother: “You know that Irene and I were planning to marry next June, well we are going to have to get married earlier”, but she wasn’t fooled. I don’t know if this was because she had faith in my, or Irene’s, respectability, or because she doubted my manhood. Anyway, she, too, was very pleased, or at least she simulated pleasure very well. So suddenly all systems were go, with me having a few weeks in each of the appropriate astronomical departments and Irene making plans for the wedding.

The event took place at St John’s Church, Polegate, on March 30th 1963. My best man was Bob Dickens. The reception was held at Herstmonceux Castle, a lovely setting which we were able to use for no charge as we worked there – a concession that did not last very long. We were due to sail for South Africa in about a week, so that was to be our honeymoon and, on the evening of the wedding, we just drove off to Folkestone and checked in at the first hotel we came across. Our suitcases had been thoroughly got at with confetti and shards from punched cards – small angular pieces of card that got everywhere and were almost impossible to remove. We were still finding them in the car boot three years later.

Next day we moved on to a Dover hotel for a couple of nights, then back to Polegate to pack for the journey and to say our goodbyes to family and friends. Also time to say farewell to this Chapter.

South Africa and early married life, 1963-1965

First a bit of background. John Radcliffe was appointed Royal Physician to King William-and-Mary in 1713 and he amassed a fortune with which he endowed the John Radcliffe Hospital, a library (the Radcliffe Camera) and still there was some left over. In the terms of the will, this could be used for a charitable, non-profit-making purpose. The trustees stretched the rules a bit to endow the Radcliffe Observatory in Oxford in 1773. At least astronomy satisfied the non-profit-making bit. Over the years, the site in Oxford became quite unsuitable for observing the night sky and the telescopes became obsolete. But the site itself had become extremely valuable. So the trustees, as imaginative as their predecessors, sold the site in 1934 and used the money to build the largest telescope in the southern hemisphere.

The Municipality of Pretoria in South Africa provided the site free, but still the money ran short and the trustees were left with a beautiful telescope – a 74-inch reflector by Grubb Parsons of Newcastle – but no means of paying for staff. This was solved by selling a third of the time on the telescope to the much bigger Royal Observatory at the Cape. The Cape Observer at the Radcliffe Observatory (to give him his full title) was traditionally supplied by the RGO, sent on a three-year tour of duty to work in Pretoria but answerable to Her Majesty’s Astronomer at the Cape – Dr Stoy. That was to be my rôle, in succession to George Harding. George’s predecessor as Cape Observer had been Patrick Wayman, now back at Herstmonceux, and I understand that it was he who recommended me for the post. He and his wife Mavis were particularly helpful before we went, filling us in on what to expect. “We only ever saw one snake [pause] in the house!”Dr Alan Hunter, Chief Assistant to the Astronomer Royal, was also very helpful, particularly in arranging for Irene to be transferred to South Africa as my assistant, retaining her grade of Scientific Assistant rather than having to take the much worse-paid post of Lady Computer as offered by the Radcliffe. My pay was enhanced by Foreign Service Allowance, which was supposed to reflect the extra cost of living in South Africa, but which, following difficulty in persuading people to go there after the Sharpville massacre in 1960, was more in the nature of a generous bribe. So we would be (relatively) rolling in it!

We sailed from Southampton on the Transvaal Castle, the newest ship of the Union Castle line. This caused a bit of a problem because Civil Service Regulations decreed that an officer of my grade should travel first, second, or third class (I forget which) and the Transvaal Castle was a one-class ship. Anyway, with the help of Harry Cook, the most generous possible interpretation of the rules was made and we had an excellent twin bedded (hardly ideal for a honeymoon, but there were no double beds on board) outside cabin on one of the higher decks. A small touch of luxury was that we each had our own bedside ’phone, though in the present mobile-swamped days this cuts little ice. Harry Cook had been of phenomenal help with all the regulations, making sure that we got such things as our tropical kit allowance and our once-in-a-career cabin trunk allowance. He also dealt with all the intricacies of exporting a car and three-quarters of a van load of effects – except that our effects were nothing like enough to fill even half a van – bills of lading and similar exotica.

Aunt Cath (she was younger than Irene, but married to Fred’s step brother, so technically an aunt) had written to the captain telling him that we were on honeymoon and could he arrange an apple-pie bed? He sent us some champagne, instead, which was much more acceptable. But the cat was out of the hat and the newness of our marital status soon became common knowledge, though we were quite happy with that. Most people head north for the northern hemisphere summer, so there were relatively few going the other way and the ship was less than half full. This had many advantages, such as no competition for the facilities and only one sitting in the restaurant. We soon developed a circle of friends, starting with those who shared our table. (Table numbers were allocated from the outset and remained fixed throughout the voyage.) One couple was Murray Armor and his wife. He was a senior administrator in Rhodesia, returning from leave. Then there was a younger couple, a now-anonymous Rhodesian District Officer and his wife. District Officers were the action men of the day, having responsibility for administering and policing vast areas. Murray lent us a book about the building of the Kariba Dam in which the DO, who then had a name, featured. When the lake behind the dam was filling, some elephants got isolated on an island which would later be submerged. DO rescued them by lassoing them and then swimming ahead of them pulling the lasso rope. Unlike the more placid Indian elephants, the African variety is not to be messed with even on dry land. It was a phenomenal achievement. He was great company and an excellent dancer, which Irene greatly appreciated as she loved dancing and, despite the efforts of Sonny Binnik, I was not.

We formed a group of six, with DO as the ringleader. We discovered the delights of the machinery in the gym, but most of it had broken down by the time we reached the Canaries. Then there was the children’s play area, which was deserted after 9 pm so we were able to play the theme from Z-cars on the jukebox until late at night. Deck games could be played without advance booking and the swimming pool was not overcrowded.

The Canary Islands made a welcome break, though two of our other friends, a solicitor and his wife, departed there. We knew we were approaching during the night when the ship started rolling for the first time. We had not appreciated how effective the stabilisers were until they had been switched off for entry into port. We went off on a taxi tour of the island, up the volcano to get a view down into it where intrepid – or foolish – farmers grew bananas. Our first experience of such exotica.

When the ship was approaching the equator, about half a dozen victims were selected to appear before King Neptune’s court at the crossing-the-line ceremony, which was to take place at the swimming pool. Irene was one of them. They were taken to the Captain’s cabin for briefing and, when asked her name, Irene automatically answered “Irene Saunders.” So the crime of which she was accused before the court was that she, Miss Saunders, was sharing a cabin with a Mr Malin. She was found guilty, of course, and was sentenced to be given a raw-egg shampoo (complete with the eggshells) followed by being thrown to the bears in the pool. There was a special ducking stool from which she was tipped backwards and set upon by the bears. In reality, their job was to make sure the duckees did not get hurt and to conduct them to the steps. All great fun, followed by a complimentary proper shampoo for Irene.In those days the voyage took fourteen days and by the end of that time we had had enough of it, even though we were on honeymoon and despite the busy social programme that was provided. Perhaps it was the first sight of the southern stars from the unlit deck of the ship that made me anxious to get to work on them. We went out and had a romantic star-gaze after a formal dance. It really was a spectacular sight with the Milky Way clearer and brighter than I had ever seen it from England. Of course it is much brighter than in the north, because the centre of the Galaxy is in the south. And there were many other new and exciting objects visible to the naked eye.

As the ship finally arrived in Cape Town, we got up before dawn at Murray’s insistence so that we could see the Sun rise over Table Mountain (the geography of Cape Town is complicated, but, trust me, the Sun really did appear from behind the mountain when viewed from the ship). Then we went back to bed until we were roused by a bearded Petty Officer from the British naval base at Simonstown. He had come aboard specially to see us safely through disembarkation. He took our passports told us to go and have a leisurely breakfast and then meet him back at the cabin. While going to breakfast, we saw Murray, the DO and their wives in a long queue waiting to get off the boat. “You should have started queuing by now” they said, “it will take you hours to get ashore.” After breakfast, the Petty Officer took our bags and led us off the ship, past the long queue that was now waiting for Customs, past our astounded friends and past the immigration officials, who simply waved us through. Ah, the advantages of working for the Admiralty!

Joe Bates, from the Herstmonceux Electronics Department, and on a three-year tour of duty at the Royal Observatory, Cape of Good Hope (to give it its full title) was there to meet us as we stepped onto South African soil. We already knew him from Herstmonceux and it was good to see a familiar face. He took over from the Petty Officer and set about clearing our car through customs. It was a complicated process which I didn’t fully understand (or even partially), but I know it involved taking a South African official out to a crayfish lunch. In an incredibly short time, we were able to collect the car from the pound and head off into our new life. Well, almost. The car had been drained of petrol in Southampton, but there was enough petrol left to get it to a petrol station, with the aid of a shunt from Joe. Then off to the Royal Observatory, Cape, to meet some more Herstmonceux friends and to report for duty.

We had a great week exploring Cape Town and being thoroughly well entertained by friends and locals, including Dr Stoy who was the kindest and gentlest of bosses. Then it was time to set off to Pretoria, about a thousand miles north east into the interior of Africa. This should have been simple as all we had to do was head north out of Cape Town and keep going, but I have already mentioned that the geography of Cape Town is peculiar, and it takes time to get used to the idea of the Sun being in the north and going round the wrong way. Anyway, before we were out of the suburbs we were hopelessly lost in the middle of a township and surrounded by feral dogs. Eventually we found the road we wanted and started to enjoy the wonderful new scenery. The Morris Minor was happy to potter along at 50 mph, but didn’t like to be hurried at any greater speed, so progress was not spectacular. Just before dusk, when we were thinking of finding somewhere to stay, we arrive in Beaufort West, just at factory closing time. We were surrounded by black workers on all forms of transport from foot to lorries and suddenly we felt all alone on a dark continent. “Carry on driving” said Irene, and I was happy to do so. Very quickly, as is the custom in Africa, it was totally dark and we felt even more isolated – what were we doing in this place? Then we saw a neon hotel sign off to the right near Richmond and headed for it. It was a comfortable and welcoming little place and, after a warm meal, we felt a lot better about things. When we went to the car next morning to continue the journey we discovered another African phenomenon – the car was covered in frost. It is said that Africa is a cold country with a hot Sun. I was constantly reminded of this while working through the night in Pretoria.

There were some more familiar faces to welcome us when we eventually arrived at the Radcliffe Observatory: George Harding, from whom I was taking over as Cape Observer, and Sheila and Phil Hill. Sheila had started work at Herstmonceux as a Scientific Assistant at the same time as Irene and they worked in the same department. Phil was a vacation student with me and had gone on to do a DPhil at Oxford before marrying Sheila (Irene was a bridesmaid and I was an usher) and getting a post-doctoral appointment at Pretoria. Sheila and Phil were on the Radcliffe staff, whereas Irene and I were still employed by the Admiralty, and the marked difference in salary, in our favour, was the cause of some envy.

There was a small building in the observatory grounds called Cape Cottage and it was intended for the use of a second Cape observer, sent up from Cape Town to share the observing duties during the long winter nights. There was no need for a second Cape observer when we first arrived, as George was still there, so Irene and I spent the first few weeks in the Cape Cottage.

It was Irene’s 23rd birthday shortly after we arrived, so obviously a present was called for. Funds were very low after wedding and transfer expenses and I had yet to receive my first pay-check in South Africa. I could have asked for an advance, but foolish pride and all that. Irene set her heart on a pendant necklace with a tiger’s eye in a silver mounting (not an actual tiger’s eye, of course, but the typically South African semi-precious gemstone of that name) so that was what she had to have. It cost more than half of all the money I had in the world, but was well worth it because it became Irene’s favourite piece of jewellery.

The observatory was on the outskirts of Pretoria next to a posh suburb called Waterkloof. The grounds housed, besides the telescope, an office block, four houses for staff (Dr Thackeray, Dr Wesselink, Dr Feast and Denis Pullin the engineer – or “Celestial Mechanic” according to the sign on his workshop door), the Cape Cottage, basic accommodation for a few of the African staff and, later, a swimming pool. The permanent residents were friendly enough, but we chose to move out into the real world and soon found a flat in Sunnyside, much nearer to the centre of town. It was also conveniently close to a good shopping centre.

On our first evening in Pretoria, after we had settled into the cottage, Phil took me over to meet the telescope in the ideal introductory conditions – that is, after dark when it was being used. It produced a mixture of feelings: excitement at the prospect of working with it, fear that I would not be able to cope and sheer wonder at the size of it. It was by far the largest telescope I had ever seen. By the end of my time there it had become an old friend with no secrets and quite a few bad habits that were mostly forgiven, but at that first meeting it was the Great Unknown.

It was not housed in a dome, but in what looked like a gasometer, though with two sections that could be moved apart to let the starlight in. This design was convenient as it housed a gantry crane that could be moved up and down, swung in and out, and traversed around the dome (as it continued to be called, despite its shape. The crane was essential for changing mirrors and shifting heavy machinery onto and off the telescope. The whole dome rotated so that the slit could move around to the part of the sky that was being observed. The telescope was the traditional open-work sort with the three-ton, six-foot diameter mirror at the bottom of the tube and a secondary mirror at the top end. It was on an offset English equatorial mount – look it up on Google if you are that interested. On the floor below the telescope was Denis’s celestial workshop, an aluminising plant (for re-coating the mirror when it needed it) and a dark room.

Transport to and from the observatory was provided in an observatory minibus driven by John, who would do the rounds morning, evening and at lunchtime, collecting and delivering staff. Most of those who didn’t live-in were more remote from the observatory than us, so we were the last to be picked up and the first to be set down. Initially we would go home for lunch (beans on toast, or similar), but after the arrival of the swimming pool, we usually took a packed lunch and incorporated a lunchtime dip.